I did the closing keynote at the first RustConf yesterday, on Rust and systems programming and accessibility and learning about concurrency and why I write about programming and a bunch of other things.

I was really delighted to be invited because I’m a huge fan of the Rust community. They’re working incredibly hard to make a language that is extremely powerful, but also easy to use, and there was a huge focus on usability and good error messages. The talks were really ambitious, friendly, and inclusive. Their challenge is “Fast, safe, productive – pick three” :).

Here’s a video & transcript of that talk (where when I say “transcript” I mean “more less what I said, kinda”).

video

transcript

You can click on any of the slides to see a big version.

I drew the slides with this Samsung tablet, and Powerpoint for android. These were the easiest slides I’ve ever made.

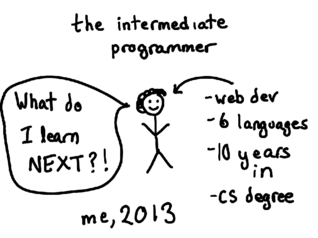

I spend a lot of my time on a comet very far away from Rust. So why am I talking to you right now?

"We see the language as empowering for a wide variety of people who might not otherwise consider themselves systems programmers."

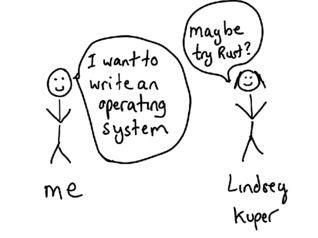

And the person who doesn't consider themselves as a systems programmer! That has TOTALLY BEEN ME. So let's talk about experiments and empowerment.So I went to the Recurse Center! RC is a 12-week programming retreat in New York where you go to learn whatever you want about programming.

It's totally self-directed, and while I was there I ended up spending a lot of time learning about operating systems, because that was the most confusing thing I could find to work on.

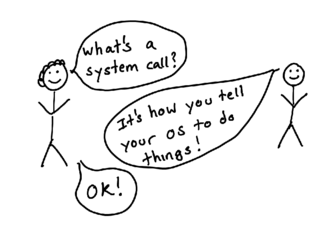

It turns out it had a pretty simplex explanation -- your operating system knows how to do things like open files, you program does not, so your program asks your operating system to do things with system calls! Like `open`.

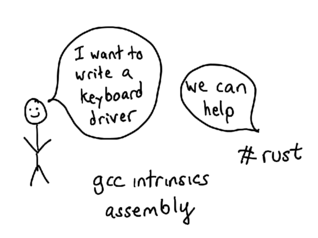

It turns out that writing an operating system in 3 weeks is actually impossible (at least for me!), so I reduced my scope a lot -- I decided to just write a keyboard driver from scratch. So my goal was, when I typed a key on my keyboard, that key would appear on my screen!

Turns out that this is not at all trivial.

So, one of the themes for this talk was "you can contribute without coding". I really believe in this -- I think that code contributions are great, don't get me wrong.

But I have basically never contributed code to an open source project (even though I'm a programmer!) and I think I've contributed a lot to open source communities.

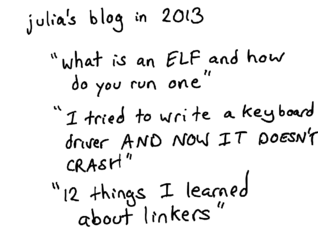

When I started doing this I discovered a really surprising thing. At the time I was writing blog posts every day about what I'd learned that day.

And even though I was a beginner to both Rust and operating systems development, it turned out that some of these blog posts were really popular! People were learning from them!

I wrote buzzfeed-style posts like "12 things I learned today about linkers", After 5 days, my OS doesn't crash when I press a key, How to run a simple ELF executable, from scratch (I don't know), and a lot more.

So this is interesting, right! To teach people it turns out you don't have to be an expert at all. Maybe it's actually even better to be a beginner!

My friend Maya jokes that I'm basically developer relations for strace.

This happened because in 2013, someone told me about strace, a program I love that traces system calls. And I was so shocked that I hadn't known about it before! So I started telling everyone.

And now all kinds of people know about strace because of me, and they have a new useful tool! So that basically makes me the inventor of strace for those people, right? :)

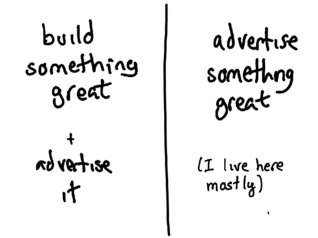

I like doing this in my spare time because I write code at work, so it's a really nice change of pace.

Writing code is a lot of work. And when you write the code, if you want people to use it, it's a lot of work to tell people about it!

So I like to skip the whole first step of writing code, and just tell people about awesome things that already exist. I'm like the most productive software developer ever.

Let's switch gears and talk about learning systems programming.

My coworker asked me the other day "I'm reading a book about Rust, what would be a good example program to write?". And this is a hard question to answer!

So here's a possible answer to that question. I think it's important to have a lot of answers like this, because there's so much to learn!

So one evening, I was at home, and I wanted to know more about concurrency.

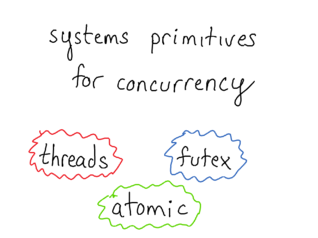

But this isn't a very specific question! A better question is -- what are the systems primitives for concurrency?

I knew that a lot of concurrent programs used the same kind of functions and ideas and systems calls. So what were those things, and how did they work?

Many concurrent programs use operating systems threads, they need to control access to resources with mutexes, and sometimes they do these "atomic instruction" things.

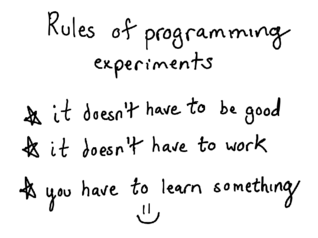

My favorite way to start out exploring idea is to write a program that doesn't work.

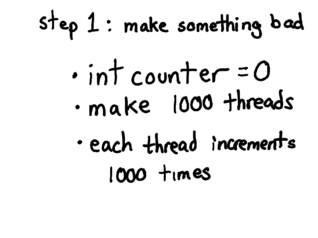

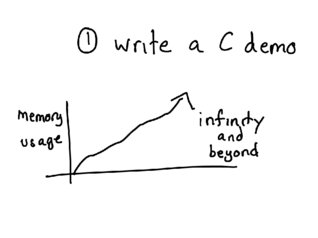

It's easy to write unsafe programs in C, so I did it in C. I made 1000 threads that each incremented the same counter 1000 times. You should get 100000 at the end, right?

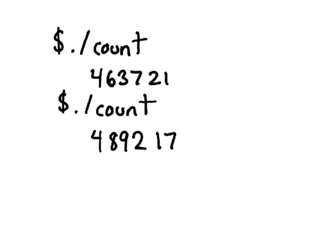

Nope! Instead we get a data race! The answer is way less than a million. This is great! I was very happy already because I'd made a race and it worked.

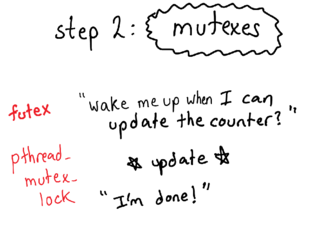

So one of the first ways to work on concurrency is mutexes, or locks. You and all the other threads have one place where you go to control who's allowed to update the counter.

I like this as a simple example because you can just get it to work and move on, or, if you want, you can go a lot deeper.

For example! To use mutexes, underneath you often use a function called pthread_mutex_lock. And it turns out that sometimes that uses the futex system call, and sometimes it doesn't! So there's all kinds of hidden complexity.

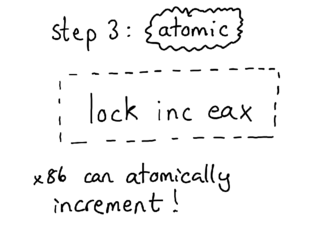

The next thing I want to talk about is atomic instructions. Basically your CPU knows how to increment counters without races -- if you say "lock inc" then it will make sure that the counter gets incremented exactly once.

So now we have a nice small exercise! This is not really that hard to do in Rust, but it introduces a lot of new ideas.

And there are a lot of opportunities for questions, right? Like, are mutexes or atomics faster? How much? Why? I love problems that you can finish pretty easily, but take farther if you want.

Now we're onto the last part of the talk.

I originally wrote "impossible problems" here. But of course all programs are technically *possible* to write!

As we're going to learn shortly, though, right now I really do not know C, and I have a day job, and so my free time for programming is not unlimited. So even if a program is *possible* for me to write, if I have to write it in C/C++, probably in practice it's not going to happen.

I'm going to tell you about how Rust helped me write a program that I wanted to write, that would have been improbable otherwise.

This where we get back to EMPOWERMENT.

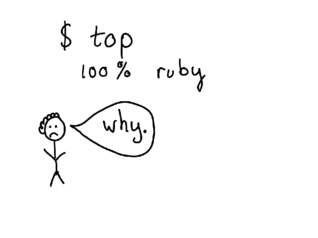

So, here's the problem I was mad about. I'd run "top" on my computer, and it would tell me Ruby was using all the CPU, and I wouldn't know why.

And the reason this made me mad, is that I could see what other programs like Chrome were doing with perf top

(cool demo of perf top goes here)

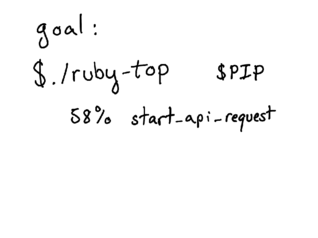

So I wanted to write a program that I could just give the PID of a Ruby process, and it would tell me the top Ruby functions that were running right now.

Is that possible? My friend Julian claimed this was totally possible and easy. So eventually I decided to try.

To do this from the outside, you have to basically spy on the internals of a running Ruby process.

The system call I used to spy is called process_vm_readv.

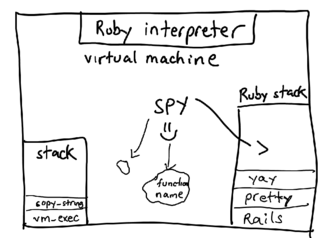

In the Ruby interpreter, you have the C stack. That has unhelpful things on it like "you're in vm_exec right now" which basically means "you're running a Ruby function"

BUT WHICH RUBY FUNCTION?!

But somewhere inside its memory, somewhere, you have the Ruby stack. That's what I wanted to get at.

I'm not going to go into the details of how this works because I don't have time, but I wrote a C demo of this program. I know how to write C! I can allocate memory in C! My demo kinda worked!

However, I do not really know how to *free* memory in C. Like, I technically know that there is a free function, but I don't have a lot of experience with it. So my program had some pretty serious memory issues almost right away.

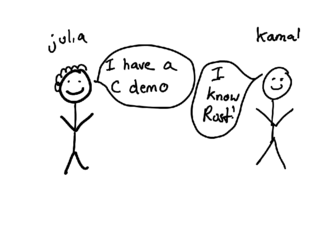

At this point I asked my partner Kamal for some help translating my program to Rust.

At the time I used bindgen and it was awesome, it took maybe a day, and now I had a Rust program that did the same thing! Except I didn't have to know how to free memory anymore.

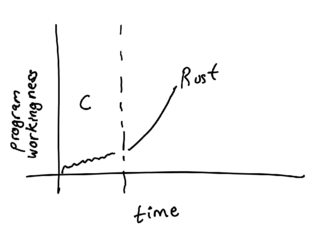

If you observe this highly scientific graph of "program workingness", you will see that my productivity went up.

I had to fight with the compiler a lot more, but I did not have to learn how to implement hashmaps from scratch. Win.

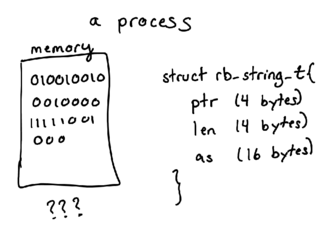

But I had one more problem. It turned out that I needed to know what the bytes in memory in my Ruby program *meant*. I wanted to know what the original struct definitions were so I could interpret all these 0s and 1s.

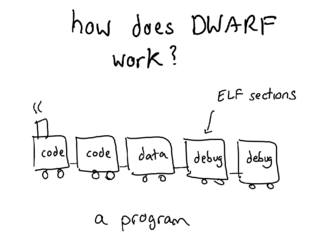

Luckily, sometimes the C compiler will save a bunch of debug information in a format called DWARF.

This basically has all the structs and saves them inside your programs! Yay! This is the best! I had hope again.

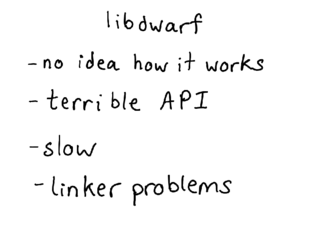

I needed a library for parsing DWARF, though. I started with trying libdwarf, and I got it maybe 90% working. But it was sort of a terrible experience.

The API was terrible, there were no docs that I could find, it was slow, I had a bad time linking the library into my Rust program.

One of the most upsetting things to me about this library is that it was really hard to understand how DWARF actually worked by looking at the interfaces it provided. I like knowing how things work.

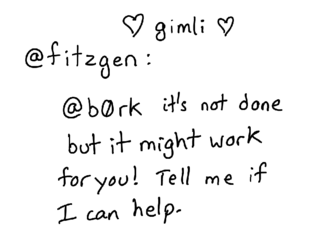

A lot of the time when I have programming problems, I complain about them on Twitter. Somebody suggested I try a Rust library called 'gimli'.

One of the maintainers, Nick Fitzgerald, told me it wasn't done but he thought it might have all the features I needed! GREAT.

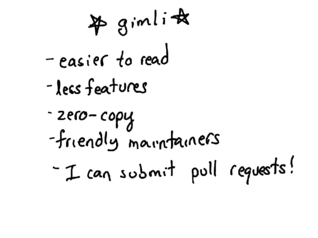

Using Gimli was a way better experience. It didn't have too much documentation either, but that was okay -- the example program they provided was really helpful, and explained how to do basically everything I needed to do.

The only thing it didn't do that I wanted was really small, and I submitted a tiny pull request to get it.

And the maintainers were really helpful! I understood DWARF better after I started working with Gimli.

"How does DWARF work" is a question pretty far out of the scope of this talk, but basically if your program is a train car (made of a bunch of ELF section), DWARF debug info is basically just a bunch of extra train cars tacked on to the end. One of the sections just basically has all the strings in your program concatenated together!

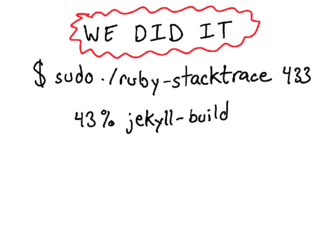

So, after this whole saga, we did it!! I worked on this a lot with Kamal and our ruby stacktrace program worked! It's on github and everything. It works on 3 computers.

(insert cool demo here)

I spend a lot of time being frustrated with the Rust compiler, but I still like it because it lets me do things I probably wouldn't get done otherwise.

I want to leave you with a few things.

One delightful thing about systems is that there's always SO MUCH MORE TO LEARN. I don't think there's any danger of any of knowing everything about systems programming any time soon.

I'm pretty sure all of you know cool things about programming that I don't know. If you like writing, this can be a great way to make the community around you know more!

One thing I really want to emphasize is -- I see a ton of resources for beginners, and I think those are really awesome.

What I don't see as much of as I'd like is resources for people who know how to program, or know Rust, and really want to take their skills to the next level. I think the Rust community is really well placed to help people do this.

Writing down information like this for developers who might already have 5 or 10 years of experiences is where I spend almost all my time.

And while you're writing down cool things to help people level up -- remember that a lot of systems things aren't really that hard. People can learn harder things than you think they can if you explain it in a way that makes sense.

I think computer networking is a really good example of this -- a lot of people get really intimidated by networking, but a lot of the core concepts like IP addresses and ports and packets are not really that hard, and once you understand them you can learn a lot.

I wrote a zine called "linux debugging tools you'll love" that talks about ngrep, tcpdump, strace, etc. And somebody tweeted at me saying he was using it to teach his 8 year old! What? So I'm not totally sure I believe that the 8 year old is using tcpdump. But maybe I'm wrong!! Who am I to say that?

So I've discovered that the audience for clear writing about systems programming is huge. A lot bigger than you might think.

I'm really happy about the Rust community because there are a ton of people in this room who know about Linux and networking and concurrency and all these topics that have historically been really hard to learn about.

But now many of you are gathered here inside this really welcoming and wonderful community! This feels magical to me and like it's going to be a really good thing for programming as a whole.

So, to close, for real, I'm excited for this to be a place where people can walk in asking "what's a system call?"

and wake up a year later knowing how to do systems programming, and thinking it wasn't really that hard.

this is a picture I commissioned of myself at the san franscisco zine festival from @ohmaipie as a wizard.