Do we think of git commits as diffs, snapshots, and/or histories?

Hello! I’ve been extremely slowly trying to figure how to explain every core concept in Git (commits! branches! remotes! the staging area!) and commits have been surprisingly tricky.

Understanding how git commits are implemented feels pretty straightforward to me (those are facts! I can look it up!), but it’s been much harder to figure out how other people think about commits. So like I’ve been doing a lot recently, I went on Mastodon and started asking some questions.

how do people think about Git commits?

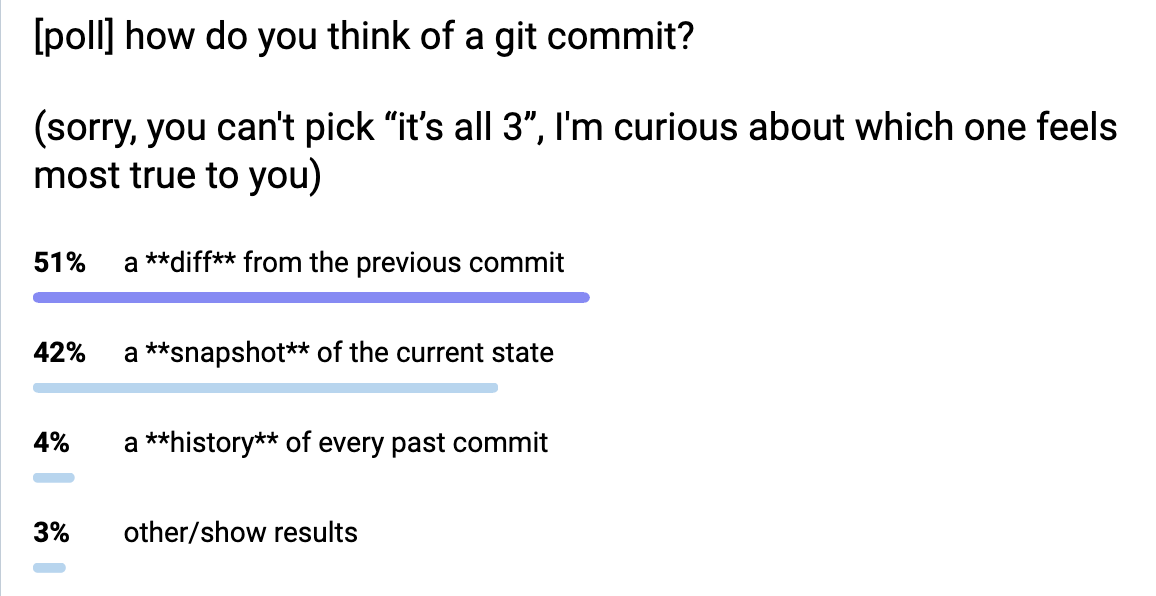

I did a highly unscientific poll on Mastodon about how people think about Git commits: is it a snapshot? is it a diff? is it a list of every previous commit? (Of course it’s legitimate to think about it as all three, but I was curious about the primary way people think about Git commits). Here it is:

The results were:

- 51% diff

- 42% snapshot

- 4% history of every previous commit

- 3% “other”

I was really surprised that it was so evenly split between diffs and snapshots. People also made some interesting kind of contradictory statements like “in my mind a commit is a diff, but I think it’s actually implemented as a snapshot” and “in my mind a commit is a snapshot, but I think it’s actually implemented as a diff”. We’ll talk more about how a commit is actually implemented later in the post.

Before we go any further: when we say “a diff” or “a snapshot”, what does that mean?

what’s a diff?

What I mean by a diff is probably obvious: it’s what you get when you run git show COMMIT_ID. For example here’s a typo fix from rbspy:

diff --git a/src/ui/summary.rs b/src/ui/summary.rs

index 5c4ff9c..3ce9b3b 100644

--- a/src/ui/summary.rs

+++ b/src/ui/summary.rs

@@ -160,7 +160,7 @@ mod tests {

";

let mut buf: Vec<u8> = Vec::new();

- stats.write(&mut buf).expect("Callgrind write failed");

+ stats.write(&mut buf).expect("summary write failed");

let actual = String::from_utf8(buf).expect("summary output not utf8");

assert_eq!(actual, expected, "Unexpected summary output");

}

You can see it on GitHub here: https://github.com/rbspy/rbspy/commit/24ad81d2439f9e63dd91cc1126ca1bb5d3a4da5b

what’s a snapshot?

When I say “a snapshot”, what I mean is “all the files that you get when you

run git checkout COMMIT_ID”.

Git often calls the list of files for a commit a “tree” (as in “directory tree”), and you can see all of the files for the above example commit here on GitHub:

https://github.com/rbspy/rbspy/tree/24ad81d2439f9e63dd91cc1126ca1bb5d3a4da5b (it’s /tree/ instead of /commit/)

is “how Git implements it” really the right way to explain it?

Probably the most common piece of advice I hear related to learning Git is “just learn how Git represents things internally, and everything will make sense”. I obviously find this perspective extremely appealing (if you’ve spent any time reading this blog, you know I love thinking about how things are implemented internally).

But as a strategy for teaching Git, it hasn’t been as successful as I’d hoped! Often I’ve eagerly started explaining “okay, so git commits are snapshots with a pointer to their parent, and then a branch is a pointer to a commit, and…”, but the person I’m trying to help will tell me that they didn’t really find that explanation that useful at all and they still don’t get it. So I’ve been considering other options.

Let’s talk about the internals a bit anyway though.

how git represents commits internally: snapshots

Internally, git represents commits as snapshots (it stores the “tree” of the current version of every file). I wrote about this in In a git repository, where do your files live?, but here’s a very quick summary of what the internal format looks like.

Here’s how a commit is represented:

$ git cat-file -p 24ad81d2439f9e63dd91cc1126ca1bb5d3a4da5b

tree e197a79bef523842c91ee06fa19a51446975ec35

parent 26707359cdf0c2db66eb1216bf7ff00eac782f65

author Adam Jensen <adam@acj.sh> 1672104452 -0500

committer Adam Jensen <adam@acj.sh> 1672104890 -0500

Fix typo in expectation message

and here’s what we get when we look at this tree object: a list of every file / subdirectory in the repository’s root directory as of that commit:

$ git cat-file -p e197a79bef523842c91ee06fa19a51446975ec35

040000 tree 2fcc102acd27df8f24ddc3867b6756ac554b33ef .cargo

040000 tree 7714769e97c483edb052ea14e7500735c04713eb .github

100644 blob ebb410eb8266a8d6fbde8a9ffaf5db54a5fc979a .gitignore

100644 blob fa1edfb73ce93054fe32d4eb35a5c4bee68c5bf5 ARCHITECTURE.md

100644 blob 9c1883ee31f4fa8b6546a7226754cfc84ada5726 CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md

100644 blob 9fac1017cb65883554f821914fac3fb713008a34 CONTRIBUTORS.md

100644 blob b009175dbcbc186fb8066344c0e899c3104f43e5 Cargo.lock

100644 blob 94b87cd2940697288e4f18530c5933f3110b405b Cargo.toml

What this means is that checking out a Git commit is always fast: it’s just as easy for Git to check out a commit from yesterday as it is to check out a commit from 1 million commits ago. Git never has to replay 10000 diffs to figure out the current state or anything, because commits just aren’t stored as diffs.

snapshots are compressed using packfiles

I just said that Git commits are snapshots, but when someone says “I think of git commits as a snapshot, but I think internally they’re actually diffs”, that’s actually kind of true too! Git commits are not represented as diffs in the sense you’re probably used to (they’re not represented on disk as a diff from the previous commit), but the basic intuition that if you’re editing a 10,000 lines 500 times, it would be inefficient to store 500 copies of that file is right.

Git does have a way of storing files as differences from other ways. This is

called “packfiles” and periodically git will do a garbage collection and

compress your data into packfiles to save disk space. When you git clone a

repository git will also compress the data.

I don’t have space for a full explanation of how packfiles work in this post (Aditya Mukerjee’s Unpacking Git packfiles is my favourite writeup of how they work). But here’s a quick summary of my understanding of how deltas work and how they’re different from diffs:

- Objects are stored as a reference to an “original file”, plus a “delta”

- the delta has a bunch of instructions like “read bytes 0 to 100, then insert bytes ‘hello there’, then read bytes 120 to 200”. It cobbles together bytes from the original plus new text. So there’s no notion of “deletions”, just copies and additions.

- I think there are less layers of deltas: I don’t know how to actually check how many layers of deltas Git actually had to go through to get a given object, but my impression is that it usually isn’t very many. Probably less than 10? I’d love to know how to actually find this out though.

- The “original file” isn’t necessarily from the previous commit, it could be anything. Maybe it could even be from a later commit? I’m not sure about that.

- There’s no “right” algorithm for how to compute deltas, Git just has some approximate heuristics

what actually happens when you do a diff is kind of weird

When I run git show SOME_COMMIT to look at the diff for a commit, what

actually happens is kind of counterintuitive. My understanding is:

- git looks in the packfiles and applies deltas to reconstruct the tree for that commit and for its parent.

- git diffs the two directory trees (the current commit’s tree, and the parent commit’s tree). Usually this is pretty fast because almost all of the files are exactly the same, so git can just compare the hashes of the identical files and do nothing almost all of the time.

- finally git shows me the diff

So it takes deltas, turns them into a snapshot, and then calculates a diff. It feels a little weird because it starts with a diff-like-thing and ends up with another diff-like-thing, but the deltas and diffs are actually totally different so it makes sense.

That said, the way I think of it is that git stores commits as snapshots and packfiles are just an implementation detail to save disk space and make clones faster. I’ve never actually needed to know how packfiles work for any practical reason, but it does help me understand how it’s possible for git commits to be snapshots without using way too much disk space.

a “wrong” mental model for git: commits are diffs

I think a pretty common “wrong” mental model for Git is:

- commits are stored as diffs from the previous commit (plus a pointer to the parent commit(s) and an author and message).

- to get the current state for a commit, Git starts at the beginning and replays all the previous commits

This model is obviously not true (in real life, commits are stored as snapshots, and diffs are calculated from those snapshots), but it seems very useful and coherent to me! It gets a little weird with merge commits, but maybe you just say it’s stored as a diff from the first parent of the merge.

I think wrong mental models are often extremely useful, and this one doesn’t seem very problematic to me for every day Git usage. I really like that it makes the thing that we deal with the most often (the diff) the most fundamental – it seems really intuitive to me.

I’ve also been thinking about other “wrong” mental models you can have about Git which seem pretty useful like:

- commit messages can be edited (they can’t really, actually you make a copy of the commit with a new message, and the old commit continues to exist)

- commits can be moved to have a different base (similarly, they’re copied)

I feel like there’s a whole very coherent “wrong” set of ideas you can have about git that are pretty well supported by Git’s UI and not very problematic most of the time. I think it can get messy when you want to undo a change or when something goes wrong though.

some advantages of “commit as diff”

Personally even though I know that in Git commits are snapshots, I probably think of them as diffs most of the time, because:

- most of the time I’m concerned with the change I’m making – if I’m just changing 1 line of code, obviously I’m mostly thinking about just that 1 line of code and not the entire current state of the codebase

- when you click on a Git commit on GitHub or use

git show, you see the diff, so it’s just what I’m used to seeing - I use rebase a lot, which is all about replaying diffs

some advantages of “commit as snapshot”

I also think about commits as snapshots sometimes though, because:

- git often gets confused about file moves: sometimes if I move a file and edit

it, Git can’t recognize that it was moved and instead will show it as

“deleted old.py, added new.py”. This is because git only stores snapshots, so

when it says “moved old.py -> new.py”, it’s just guessing because the

contents of

old.pyandnew.pyare similar. - it’s conceptually much easier to think about what

git checkout COMMIT_IDis doing (the idea of replaying 10000 commits just feels stressful to me) - merge commits kind of make more sense to me as snapshots, because the merged commit can actually be literally anything (it’s just a new snapshot!). It helps me understand why you can make arbitrary changes when you’re resolving a merge conflict, and why it’s so important to be careful about conflict resolution.

some other ways to think about commits

Some folks in the Mastodon replies also mentioned:

- “extra” out-of-band information about the commit, like an email or a GitHub pull request or just a conversation you had with a coworker

- thinking about a diff as a “before state + after state”

- and of course, that lots of people think of commits in lots of different ways depending on the situation

some other words people use to talk about commits might be less ambiguous:

- “revision” (seems more like a snapshot)

- “patch” (seems more like a diff)

that’s all for now!

It’s been very difficult for me to get a sense of what different mental models people have for git. It’s especially tricky because people get really into policing “wrong” mental models even though those “wrong” models are often really useful, so folks are reluctant to share their “wrong” ideas for fear of some Git Explainer coming out of the woodwork to explain to them why they’re Wrong. (these Git Explainers are often well-intentioned, but it still has a chilling effect either way)

But I’ve been learning a lot! I still don’t feel totally clear about how I want to talk about commits, but we’ll get there eventually.

Thanks to Marco Rogers, Marie Flanagan, and everyone on Mastodon for talking to me about git commits.