git branches: intuition & reality

Hello! I’ve been working on writing a zine about git so I’ve been thinking about git branches a lot. I keep hearing from people that they find the way git branches work to be counterintuitive. It got me thinking: what might an “intuitive” notion of a branch be, and how is it different from how git actually works?

So in this post I want to briefly talk about

- an intuitive mental model I think many people have

- how git actually represents branches internally (“branches are a pointer to a commit” etc)

- how the “intuitive model” and the real way it works are actually pretty closely related

- some limits of the intuitive model and why it might cause problems

Nothing in this post is remotely groundbreaking so I’m going to try to keep it pretty short.

an intuitive model of a branch

Of course, people have many different intuitions about branches. Here’s the one that I think corresponds most closely to the physical “a branch of an apple tree” metaphor.

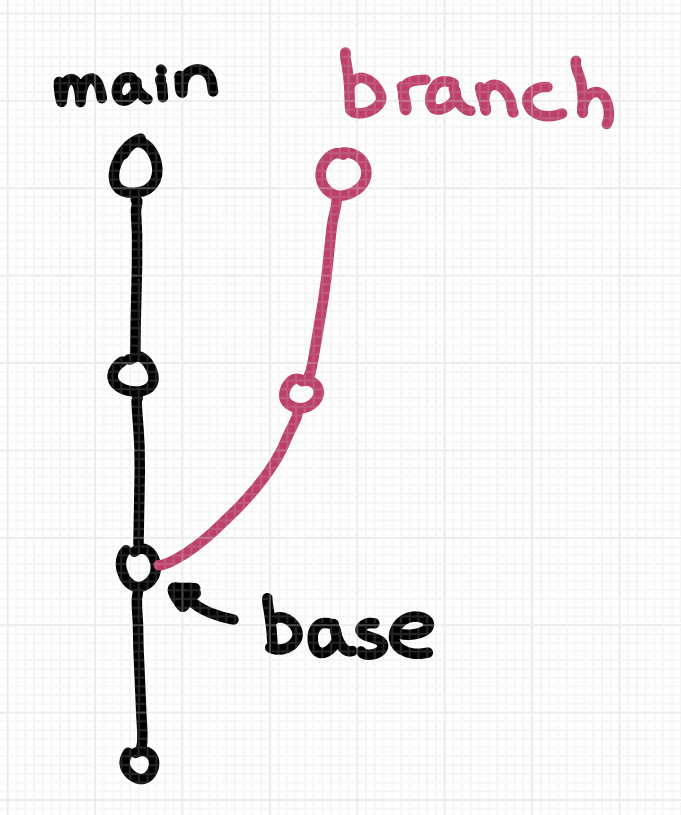

My guess is that a lot of people think about a git branch like this: the 2 commits in pink in this picture are on a “branch”.

I think there are two important things about this diagram:

- the branch has 2 commits on it

- the branch has a “parent” (

main) which it’s an offshoot of

That seems pretty reasonable, but that’s not how git defines a branch – most importantly, git doesn’t have any concept of a branch’s “parent”. So how does git define a branch?

in git, a branch is the full history

In git, a branch is the full history of every previous commit, not just the “offshoot” commits. So in our picture above both branches (main and branch) have 4 commits on them.

I made an example repository at https://github.com/jvns/branch-example which has its branches set up the same way as in the picture above. Let’s look at the 2 branches:

main has 4 commits on it:

$ git log --oneline main

70f727a d

f654888 c

3997a46 b

a74606f a

and mybranch has 4 commits on it too. The bottom two commits are shared

between both branches.

$ git log --oneline mybranch

13cb960 y

9554dab x

3997a46 b

a74606f a

So mybranch has 4 commits on it, not just the 2 commits 13cb960 and 9554dab that are “offshoot” commits.

You can get git to draw all the commits on both branches like this:

$ git log --all --oneline --graph

* 70f727a (HEAD -> main, origin/main) d

* f654888 c

| * 13cb960 (origin/mybranch, mybranch) y

| * 9554dab x

|/

* 3997a46 b

* a74606f a

a branch is stored as a commit ID

Internally in git, branches are stored as tiny text files which have a commit ID in them. That commit is the latest commit on the branch. This is the “technically correct” definition I was talking about at the beginning.

Let’s look at the text files for main and mybranch in our example repo:

$ cat .git/refs/heads/main

70f727acbe9ea3e3ed3092605721d2eda8ebb3f4

$ cat .git/refs/heads/mybranch

13cb960ad86c78bfa2a85de21cd54818105692bc

This makes sense: 70f727 is the latest commit on main and 13cb96 is the latest commit on mybranch.

The reason this works is that every commit contains a pointer to its parent(s), so git can follow the chain of pointers to get every commit on the branch.

Like I mentioned before, the thing that’s missing here is any relationship at

all between these two branches. There’s no indication that mybranch is an

offshoot of main.

Now that we’ve talked about how the intuitive notion of a branch is “wrong”, I want to talk about how it’s also right in some very important ways.

people’s intuition is usually not that wrong

I think it’s pretty popular to tell people that their intuition about git is “wrong”. I find that kind of silly – in general, even if people’s intuition about a topic is technically incorrect in some ways, people usually have the intuition they do for very legitimate reasons! “Wrong” models can be super useful.

So let’s talk about 3 ways the intuitive “offshoot” notion of a branch matches up very closely with how we actually use git in practice.

rebases use the “intuitive” notion of a branch

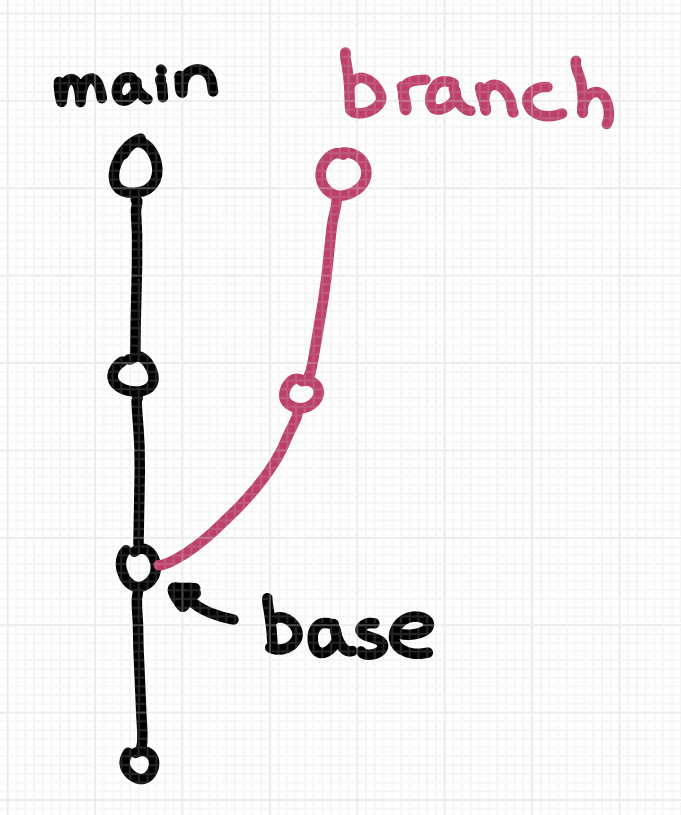

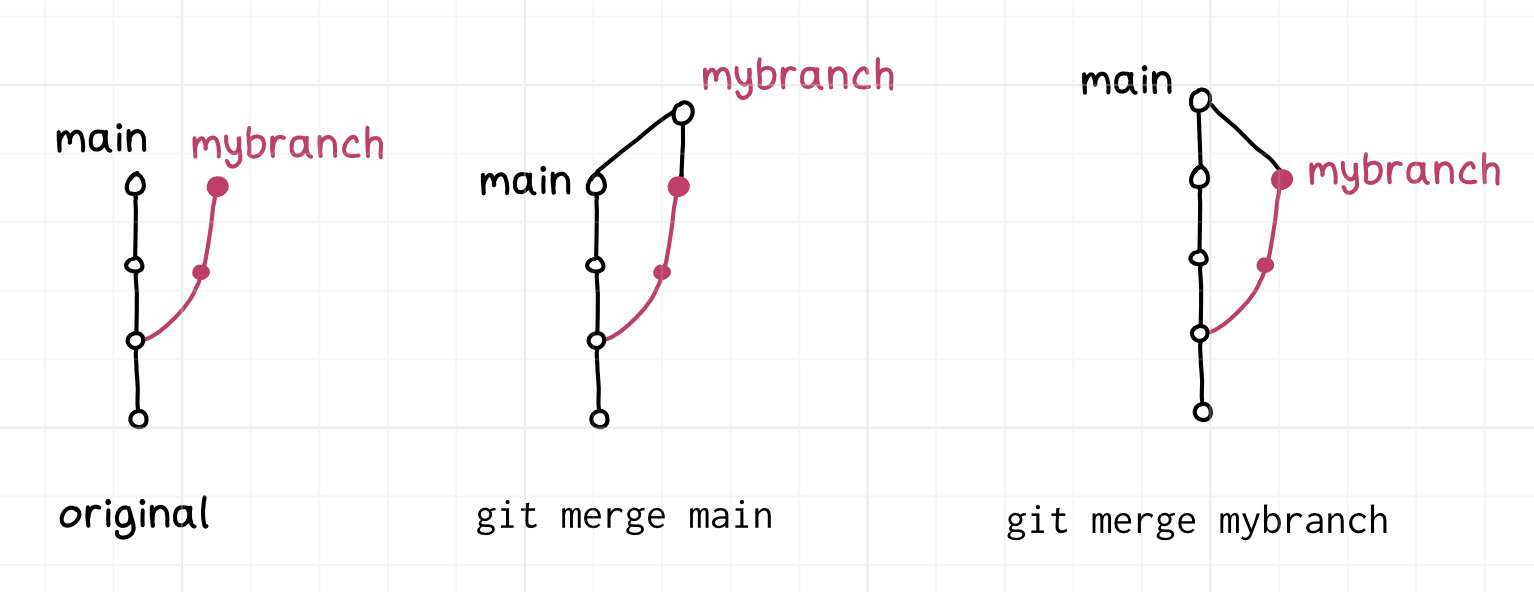

Now let’s go back to our original picture.

When you rebase mybranch on main, it takes the commits on the “intuitive”

branch (just the 2 pink commits) and replays them onto main.

The result is that just the 2 (x and y) get copied. Here’s what that looks like:

$ git switch mybranch

$ git rebase main

$ git log --oneline mybranch

952fa64 (HEAD -> mybranch) y

7d50681 x

70f727a (origin/main, main) d

f654888 c

3997a46 b

a74606f a

Here git rebase has created two new commits (952fa64 and 7d50681) whose

information comes from the previous two x and y commits.

So the intuitive model isn’t THAT wrong! It tells you exactly what happens in a rebase.

But because git doesn’t know that mybranch is an offshoot of main, you need

to tell it explicitly where to rebase the branch.

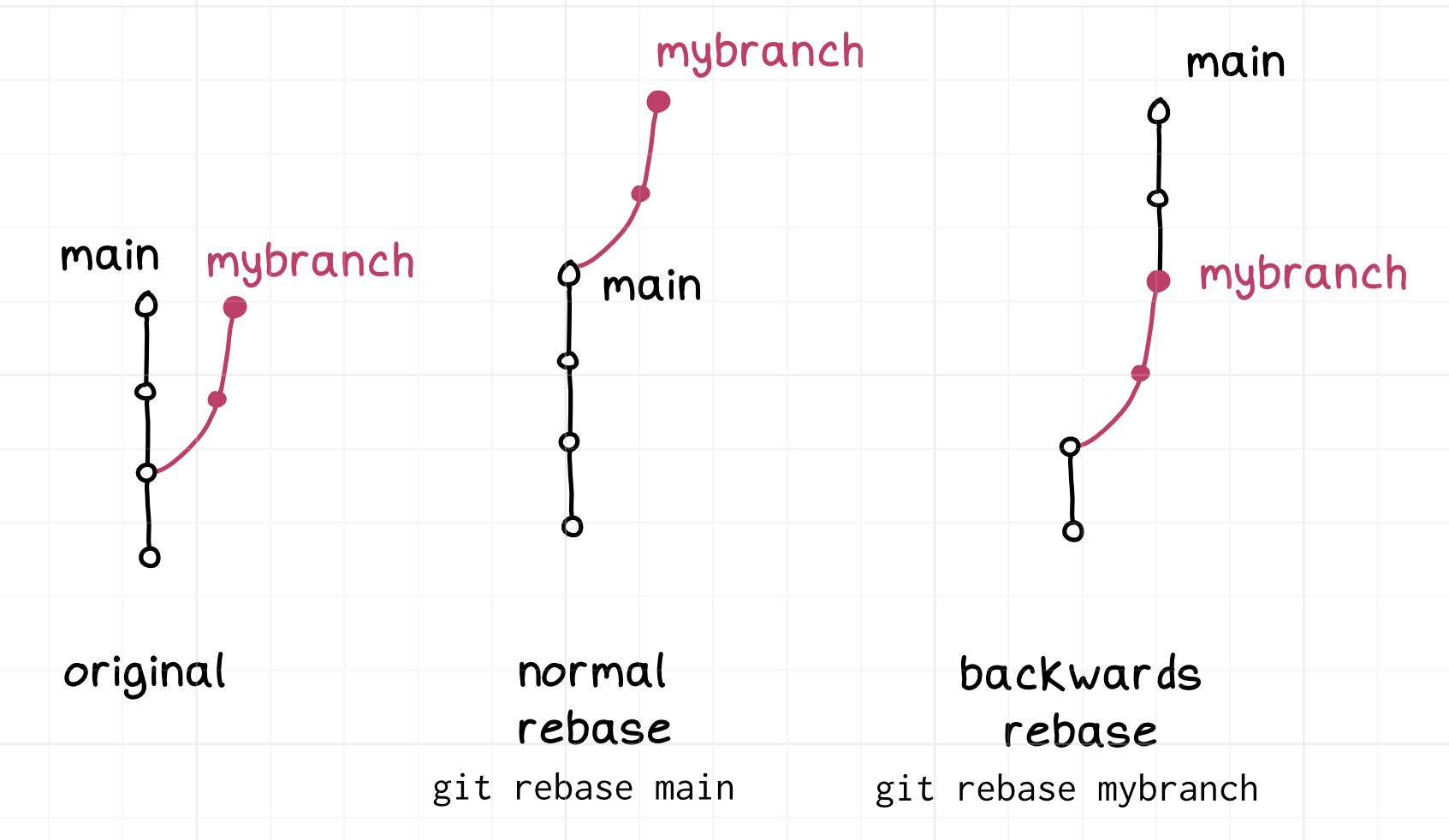

merges use the “intuitive” notion of a branch too

Merges don’t copy commits, but they do need a “base” commit: the way merges work is that it looks at two sets of changes (starting from the shared base) and then merges them.

Let’s undo the rebase we just did and then see what the merge base is.

$ git switch mybranch

$ git reset --hard 13cb960 # undo the rebase

$ git merge-base main mybranch

3997a466c50d2618f10d435d36ef12d5c6f62f57

This gives us the “base” commit where our branch branched off, 3997a4.

That’s exactly the commit you would think it might be based on our intuitive

picture.

github pull requests also use the intuitive idea

If we create a pull request on GitHub to merge mybranch into main, it’ll

also show us 2 commits: the commits x and y. That makes sense and also

matches our intuitive notion of a branch.

I assume if you make a merge request on GitLab it shows you something similar.

intuition is pretty good, but it has some limits

This leaves our intuitive definition of a branch looking pretty good actually! The “intuitive” idea of what a branch is matches exactly with how merges and rebases and GitHub pull requests work.

You do need to explicitly

specify the other branch when merging or rebasing or making a pull request (like git rebase main),

because git doesn’t know what branch you think your offshoot is based on.

But the intuitive notion of a branch has one fairly serious problem: the way

you intuitively think about main and an offshoot branch are very different,

and git doesn’t know that.

So let’s talk about the different kinds of git branches.

trunk and offshoot branches

To a human, main and mybranch are pretty different, and you probably have

pretty different intentions around how you want to use them.

I think it’s pretty normal to think of some branches as being “trunk” branches, and some branches as being “offshoots”. Also you can have an offshoot of an offshoot.

Of course, git itself doesn’t make any such distinctions (the term “offshoot” is one I just made up!), but what kind of a branch it is definitely affects how you treat it.

For example:

- you might rebase

mybranchontomainbut you probably wouldn’t rebasemainontomybranch– that would be weird! - in general people are much more careful around rewriting the history on “trunk” branches than short-lived offshoot branches

git lets you do rebases “backwards”

One thing I think throws people off about git is – because git doesn’t have any notion of whether a branch is an “offshoot” of another branch, it won’t give you any guidance about if/when it’s appropriate to rebase branch X on branch Y. You just have to know.

for example, you can do either:

$ git checkout main

$ git rebase mybranch

or

$ git checkout mybranch

$ git rebase main

Git will happily let you do either one, even though in this case git rebase main is

extremely normal and git rebase mybranch is pretty weird. A lot of people

said they found this confusing so here’s a picture of the two kinds of rebases:

Similarly, you can do merges “backwards”, though that’s much more normal than

doing a backwards rebase – merging mybranch into main and main into

mybranch are both useful things to do for different reasons.

Here’s a diagram of the two ways you can merge:

git’s lack of hierarchy between branches is a little weird

I hear the statement “the main branch is not special” a lot and I’ve been

puzzled about it – in most of the repositories I work in, main is

pretty special! Why are people saying it’s not?

I think the point is that even though branches do have relationships

between them (main is often special!), git doesn’t know anything about those

relationships.

You have to tell git explicitly about the relationship between branches every

single time you run a git command like git rebase or git merge, and if you

make a mistake things can get really weird.

I don’t know whether git’s design here is “right” or “wrong” (it definitely has some pros and cons, and I’m very tired of reading endless arguments about it), but I do think it’s surprising to a lot of people for good reason.

git’s UI around branches is weird too

Let’s say you want to look at just the “offshoot” commits on a branch, which as we’ve discussed is a completely normal thing to want.

Here’s how to see just the 2 offshoot commits on our branch with git log:

$ git switch mybranch

$ git log main..mybranch --oneline

13cb960 (HEAD -> mybranch, origin/mybranch) y

9554dab x

You can look at the combined diff for those same 2 commits with git diff like this:

$ git diff main...mybranch

So to see the 2 commits x and y with git log, you need to use 2 dots

(..), but to look at the same commits with git diff, you need to use 3 dots

(...).

Personally I can never remember what .. and ... mean so I just avoid

them completely even though in principle they seem useful.

in GitHub, the default branch is special

Also, it’s worth mentioning that GitHub does have a “special branch”: every

github repo has a “default branch” (in git terms, it’s what HEAD points at),

which is special in the following ways:

- it’s what you check out when you

git clonethe repository - it’s the default destination for pull requests

- github will suggest that you protect the default branch from force pushes

and probably even more that I’m not thinking of.

that’s all!

This all seems extremely obvious in retrospect, but it took me a long time to figure out what a more “intuitive” idea of a branch even might be because I was so used to the technical “a branch is a reference to a commit” definition.

I also hadn’t really thought about how git makes you tell it about the

hierarchy between your branches every time you run a git rebase or git merge command – for me it’s second nature to do that and it’s not a big deal,

but now that I’m thinking about it, it’s pretty easy to see how somebody could

get mixed up.