Fast integer sets with Roaring Bitmaps (and, making friends with your modern CPU)

I went to the Papers we Love Montreal meetup this week where Daniel Lemire spoke about roaring bitmaps, and it was AWESOME.

I learned about a cool new data structure, why sets of integers are super important, how modern CPUs are different from they were in the 90s, and how we should maybe think about that when designing data structures.

integer sets (TIL hash sets aren’t fast)

The talk was about building integer sets (like {1,28823,24,514}) that let you do really really fast intersections & unions & other set operations.

But why even care about integer sets? I was super confused about this at the beginning of the talk.

Well, suppose you’re building a database! Then you need to run queries like select * from people where name = 'julia' and country = 'canada'. This involves finding all the rows where name = 'julia' and where country = 'canada' and taking a set intersection! And the rows IDs are integers.

You might have millions of rows in your database that match, so both the size of the set in memory and the speed of the set intersection are important! A fast integer set library here will really help you.

One of the big takeaways for me in this talk was “whoa, hashsets are not fast. okay.” It turns out there are much much faster ways to represent large sets!

bitmaps

Here’s the basic story about how to make fast integer sets!

To represent the set [0,1,2,5], you don’t need 4 integers! (128 bits) Instead, you can just store the bits 111001 (set the bit 5 to 1 to indicate that 5 is in the set!). That’s a “bitmap” or “bitset”, and it only uses 6 bits. AMAZING.

Taking ‘AND’ or ‘OR’ of two bitmaps corresponds to set intersection or union, and is extremely wizard fast. Even faster than you might think! This is where the talk got really surprising to me, so we’re going to take a break and talk about CPUs for a while.

modern CPUs and parallelization (but not the kind you think)

I have this idea in my head that my CPU can do 2.7 billion instructions a second (that’s what 2.7 GHz means, right?). But I learned this is not actually really true! It does 2.7 billion cycles a second, but can potentially do way more instructions than that. Sometimes.

Imagine two different programs. In the first one, you’re doing something dead-simple like taking the AND of a bunch of bits. In the second program, you have tons of branching, and what you do with the end of the data depends on what the beginning of the data is.

The first one is definitely easier to parallelize! But usually when I hear people talk about parallelization, they mean splitting a computation across many CPU cores, or many computers. That’s not what this is about.

This is about doing more than one instruction per CPU cycle, on a single core, in a single thread. I still don’t understand very much about modern CPU architecture (Dan Luu writes cool blog posts about that, though). Let’s see a short experiment with that in action.

some CPU cycle math

In Computers are fast, we looked at summing the bytes in a file as fast as possible. What’s up with our CPU cycles, though? We can find out with perf stat:

$ perf stat ./bytesum_intrinsics The\ Newsroom\ S01E04.mp4

Performance counter stats for './bytesum_intrinsics The Newsroom S01E04.mp4':

783,592,910 cycles # 2.735 GHz

472,822,242 stalled-cycles-frontend # 60.34% frontend cycles idle

1,126,180,100 instructions # 1.44 insns per cycle

31,039 branch-misses # 0.02% of all branches

0.288103005 seconds time elapsed

My laptop’s clock speed is 2.735 GHz. That means in 0.288103 seconds it has time for about 780,000,000 cycles (do the math! it checks out.) Not-coincidentally, that’s exactly how many cycles perf reports the program using. But cycles are not instructions!! My understanding of modern CPUs is – old CPUs used to do only one instruction per cycle, and it was easy to reason about. New CPU have “instruction pipelines” and can do LOTS. I don’t actually know what the limit is.

For this program, it’s doing 1.4 instructions per cycle. I have no idea if that’s good, or why. If I look at perf stat ls, it does 0.6 instructions per cycle. That’s more than 2x less! In the talk, Lemire said that you can get up to an 8x speed increase by doing more instructions per cycle!

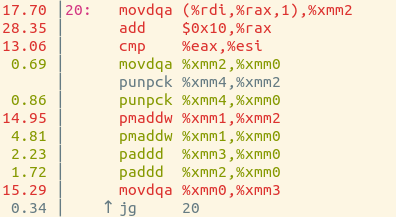

Here’s the disassembly of bytesum_intrinsics, and which instructions it spends the most time on (the numbers on the right are percentages). Dan Luu would probably be able to interpret this and tell me what’s going on, but I don’t know how.

Roaring Bitmaps: a library for compressed bitmaps

Okay, back to bitmaps!

If you want to represent the set {0,1,100000000} with a bitmap, then you have a problem. You don’t want to use 100000000 bits to represent 3 elements. So compression of bitmaps is a big deal. The Roaring Bitmap library gives you a data structure and a bunch of algorithms to take the intersection and union of compressed bitmaps fast. He said they can usually use 2-3 bits per integer they store?! I’m not going to explain how it works at all – read roaringbitmap.org or the github repository’s README if you want to know more.

modern CPUs & roaring bitmaps

What does all this talk of CPUs have to do with bitmaps, though?

Basically they designed the roaring bitmaps data structure so that the CPU can do less instructions (using single-instruction-multiple-data/SIMD instructions that let you operate on 128 bits at a time) and then additionally do lots of instructions per cycle (good parallelization!). I thought this was super awesome.

He showed a lot of really great benchmark results, and I felt pretty convinced that this is a good library.

The whole goal of the Papers We Love meetup is to show programmers work academics are doing that can actually help them write programs. This was a fantastic example of that.