Winning the bias-variance tradeoff

Machine learning is a strange mix of math and weird heuristics. When I started studying machine learning, I was SO FRUSTRATED. Everything was “well it works in practice” and so little of it was math. I was a pure math major at the time, so arguments like “well it works in practice” made me REALLY MAD.

I’d kind of given up on having a better theoretical understanding of machine learning. It was working really well in practice for me, after all! But then I met the bias-variance decomposition.

The bias-variance decomposition is a small piece of math that actually explains why some things in machine learning work!

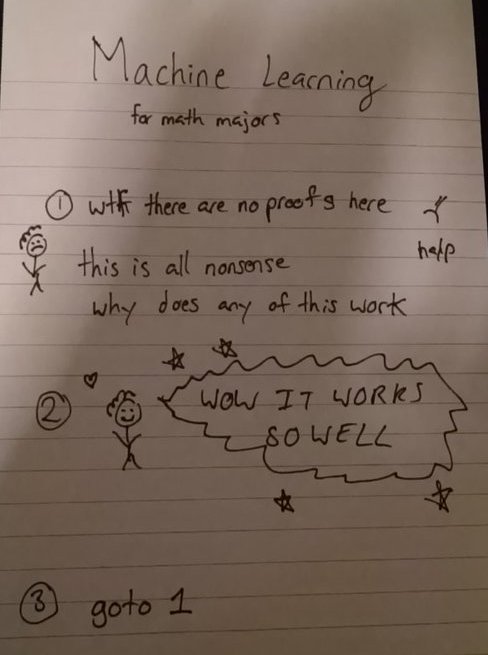

my feelings about machine learning in a picture

The bias-variance decomposition gives you a framework for how to think about model error and overfitting, and it explains why techniques like model ensembles and ridge regression result in lower error (the tradeoff is a tradeoff you can WIN). I finally learned about it last week and it felt life-changing. I think it’s going to help me build better models, and it can help you too!

I’ve annotated each section by whether it’s math or whether it a “works in practice” heuristic (aka bullshit, but useful bullshit).

Bias and variance (math)

I first took a machine learning class in 2011. I only understood what bias and variance were last week, after reading An Introduction to Statistical Learning, which is an EXCELLENT book, along with its more advanced companion. Here’s the story. I’m going to be a bit handwavy with the theorems & definitions through all of this, because the sections in those books are excellent and they’re free online PDFs. Please go there if you need more rigor! I’ll do my best to be reasonably clear.

The setup: Suppose we have all of the possible training data for a model, and a model training method (like linear regression). We’re going to look at what happens for a specific training point $$x_0$$.

Take a list of all training sets, and for each training set train a model $$M$$. Then we can look at the distribution of predictions $$M(x_0)$$ for each model. (see Statistical learning theory if you’re super interested in the theoretical foundations for machine learning)

The best case scenario: For every model we train, $$M(x_0)$$ is always the same no matter what training set we picked, and always correct. The worst case scenario: it’s always changing and always totally wrong. In reality: you have some probability distribution of predicted values.

Variance is the variance of this probability distribution of predictions across all models (how different are the values from each other?)

This is incredibly important: if every model you train makes totally different predictions, you’re in big trouble! Those predictions are definitely not correct.

On variance & overfitting: I keep hearing that high variance and overfitting are the same thing, and it makes sense to me. Overfitting is an idea, not a well-defined quantity, and if your modelling method gives you completely different results for every set of training data – I’d call that overfit. So I’m okay defining overfitting and variance to be the same thing.

Measuring variance: Variance is cool because you have some prayer of approximating it for your actual models! You could imagine training your model on different training subsets, and seeing how different the predictions are.

Bias is the difference between the mean of this probability distribution and the actual correct value. Do the models on average predict the right thing for that point?

Worst case: If you have a relationship that is totally nonlinear, and you try to use a linear model, your bias is definitely going to be high. It’s impossible to fit a correct model!

Best case: If you have a true linear relationship, and you fit a linear model with least squares regression, your bias for every point is zero. 0! unbiased! On average you’re always going to be exactly correct. But that doesn’t mean least squares regression is the best method! We’ll explain why in the next section =D =D

On complexity & bias: People say that more complex models (with more parameters) have lower bias. As far as I can tell this is something that’s likely to be true but does not have any math behind it. If there is math that says this is true I would love to know.

Measuring bias: I have no idea how to measure bias in the real world. My impression is people mostly guess at whether a model’s bias is high or low.

The bias-variance decomposition (math)

This is a theorem that you can find in An Introduction to Statistical Learning. This is math so it will never let us down ❤. It basically says that the error at a point is the

Err(x) = Bias^2 + Variance + Irreducible Error

The actual theorem statement

Denote the variable we are trying to predict as $$Y$$ and our covariates as $$X$$. Assume that there is a relationship relating one to the other such as $$Y=f(X)+\epsilon$$ where the error term $$\epsilon$$ is normally distributed with a mean of zero like so: $$\epsilon \sim N(0,\sigma_\epsilon)$$.

We may estimate a model $$\hat{f}(X)$$ of $$f(X)$$ using linear regressions or another modeling technique. In this case, the expected squared prediction error at a point $$x$$ is:

$$Err(x)=E[(Y - \hat{f}(x))^2]$$

This error may then be decomposed into bias and variance components:

$$Err(x)=(E[\hat{f}(x)] - f(x))^2+E[\hat{f}(x) - E[\hat{f}(x)]]^2+\sigma^2\epsilon$$

or in other words

Err(x) = Bias^2 + Variance + Irreducible Error

This is awesome. It means that every time we have error, it’s either because of bias or because of variance.

Heuristic warning: From now on, I’m going to talk about the bias and variance of a model. If you’ve reading carefully, you’ll notice that this doesn’t quite make sense: we’ve only defined bias and variance for a modelling method and a specific input to that model (we took the variance of $$M(x_0)$$ over all models $$M$$). All the arguments we’re going to make from now on are heuristic and not math, so we’re going to start being sloppy with the math.

The bias-variance tradeoff (heuristic)

Now we get to the cool part: the bias-variance tradeoff! As with many cool things in machine learning, the theoretical foundation here is a little shaky.

There’s no math reason I know of you have to have a tradeoff between bias and variance (if you know one, tell me!). In an ideal world, you could just train a model with low variance and low bias and win at life.

In the real world, however, we do not have magical model training methods :(. And often what people observe in practice is that as you increase the complexity of a kind of model (by training deeper decision trees, for instance), the bias decreases and the variance increases. This is the “bias-variance tradeoff”!

But just knowing that isn’t so useful. So what?

It turns out that thinking model performance in terms of a tradeoff between bias and variance can help us build better models!

Winning the bias-variance tradeoff: Ensembles!

The whole reason we’re talking about this is so we can build machine learning models with less errors. Machine learning people frequently use ensembles: take 10 or 100 models and average their results together to get a better model. For the longest time I had no idea why it worked! Here’s why.

Ensembles are based on math! In general, if I have $$n$$ independent samples from a probability distribution with variance $$\sigma$$ and mean $$\mu$$, and I average them, then the new mean is the same ($$\mu$$), but the new variance will be reduced! ($$\frac{\sigma}{n}$$).

In general if my samples have some correlation $$\rho$$, the reduction in variance depends on the correlation (a low correlation means a big reduction in variance)! This is all math.

Now, suppose you have a way to generate a model which has low bias and high variance. The canonical example of this is supposedly a deep decision tree, though I’m not aware of any math showing that decision trees have low bias.

Then if you can “average” 100 models generated in the same way, then your final model should have the same bias (mean), but lower variance! Because of the bias-variance decomposition, this means that it’s BETTER (the overall error is lower!). Yay! Further, the amount of variance reduction you get depends on the correlation between the 100 models.

This is why random forests work! Random forests take a bunch of decision trees (low bias, high variance), average them (lower variance!). And they use an extra trick (select a random subset of features when splitting) to reduce the correlation between the trees (extra lower variance!!!).

Understanding why ensembles work is awesome – it means that if an ensemble method isn’t helping you, you can understand why! It’s probably because the correlation between the models in your ensemble is too high.

Winning the bias-variance tradeoff: Regularization!

And there’s a second way to win! I honestly don’t really understand regularization yet, so I’m not going to try to explain the math at all (try Elements of Statistical Learning instead).

But I can talk about the idea for a minute! First, I want to tell you about the James–Stein estimator1. Suppose you’re trying to estimate the mean of a bunch of random vectors. The normal (unbiased!) way to estimate the true mean is to, well, take the mean of those random vectors! Awesome. You might expect that you can’t do better. BUT YOU CAN. The James-Stein estimator is a way to estimate the mean that gives you lower error. It’s a biased estimator (so on average it won’t give you a correct result), but its error is lower. This is amazing.

Model regularization is has the same effect – basically you solve a different optimization where you constrain the parameters you’re allowed to use. You end up increasing your bias and lowering the variance. And then you can end up winning and ending up with a lower overall error, if you’ve lowered the variance by more than you increased the bias!

Since I don’t understand how regularization works yet and have never used it, I also don’t know how to debug regularization (if you try regularization and it doesn’t making your model better, how can you tell why not?!). If you know how to debug regularization I’d love to know.

learning some math = ❤

I still find it kind of frustrating how heuristic most of these arguments are. Machine learning is an empirical game! But knowing a little more of the math makes me feel a little more comfortable. Not knowing how machine learning methods work means I can’t debug them, and that means I can’t be amazing. which obviously isn’t acceptable :D

If you know more math that helps you debug your machine learning models and explain their performance, please tell me!

Thanks to Max McCrea for reading this, and for Stephen Tu for helping me understand the math here and introducing me to statistical learning theory.

{% include katex_render.html %}

-

Do you know about the Princeton Companion to Mathematics? It’s literally a book that will explain EVERYTHING IN MATH TO YOU. It’s so fun, super well-written, and it taught me about the James-Stein estimator. It’s written at a level so that someone with a pure math degree should find it approachable (so, it’s perfect for me <3). ↩︎